Brokenness in Family Life: Insights From The Theology Of The Body

Peter Kahn FAITH MAGAZINE November - December 2014

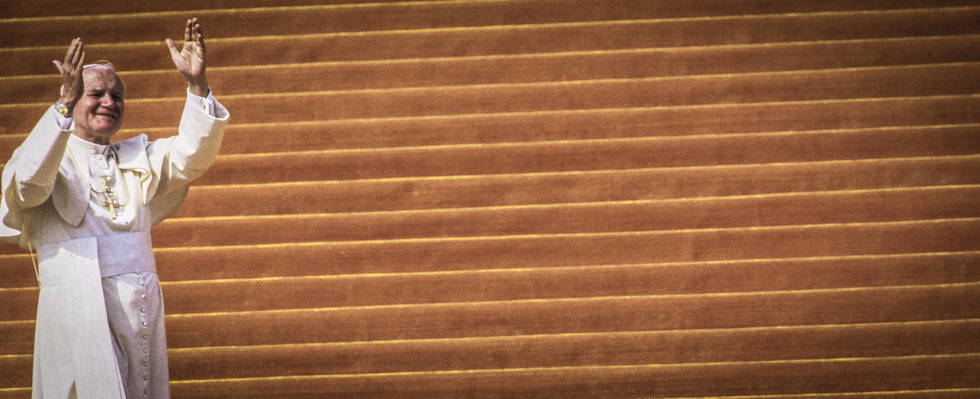

While the Synod of Bishops in Rome considered the breakdown of the modern family, Peter Khan believes there are many insights and solutions to be offered by St Pope John Paul II’s Theology of the Body.

A great deal of attention has focused recently on the difficulties and brokenness that we experience in our most intimate relationships with each other. The Extraordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops on the Family was convened in large part to consider how the Church should best exercise pastoral care in these matters. The canonical processes that are involved have received particular attention, as have the difficulties themselves. But it remains important to continue to explore the theological basis for pastoral responses. It is now quite widely accepted that Saint John Paul’s theology of the body represents the most substantive development that the Church has seen in recent years in our understanding of human sexuality. This is a corpus of theology that warrants further exploration in relation to the specific challenges that the Synod has been facing.

In this article, I would like to draw inspiration from the theology of the body to consider human brokenness in family life. José Granados has pointed out in the journal Communio that the theology of the body has particular relevance for a theology of suffering.1 He argues that St John Paul’s earlier apostolic letter Salvifici Doloris highlights the need to consider the role of self-giving in any response to suffering, with clear links to the theology of the body. More specifically, Granados suggests that an entire chapter remains to be written in the Pope’s theology of the body, namely “the transition between the fallen and redeemed states of mankind” (p540).2 The recent Synod on the family has indeed partly focused its deliberations on this transition, particularly through the notion of the law of graduality. This law is taken to incorporate the idea that love and holiness may still be present even where one does not fully realise the ideal vision of the Christian family. The idea comes in part from St John Paul’s apostolic exhortation Familiaris Consortio, in which the pope indicated that as human persons we know, love and accomplish moral goodness in stages of growth. There may be a great deal to gain from considering this transition in relation to the theology of the body.

Granados notes that the transition begins in earnest with Abraham. However, it is also clear that many distinctive aspects of the original experience of Adam and Eve are only rediscovered by Abraham’s descendants. This is especially the case with Jacob, who is synonymous with the people of Israel. I explore ways in which Jacob’s work reflected life as it was in the beginning in my booklet Work and the Christian Family.3 Here, though, we take as our starting point the text from the third chapter of Genesis that focuses on the entry of suffering into our family relationships. We then develop our understanding by considering specific biblical figures, where we see this transition occur from a fallen state to a redeemed state. This approach further follows the model that Saint John Paul adopted in his consideration of the relationship between Tobias and Sarah, a consideration that features in the theology of the body.4 Are there ways in which we can see these biblical figures enter into life as God intended it in the beginning? If this is the case, we may be able to understand more deeply God’s intentions with regard to human brokenness in today’s world. My forthcoming booklet Facing Difficulties in Christian Family Life5 also explores how families today are able to rediscover life as God intended in light of these biblical figures, but here we concentrate on drawing out the connections with the theology of the body itself.

To the Woman He Said

We start with the biblical text that announces the entry of suffering into the world: “To the woman he said: ‘I will multiply your pains in childbearing; you shall give birth to your children in pain. Your yearning shall be for your husband, yet he will lord it over you’ ” (Gen 3:14). It is certainly the case that suffering can arise for us through children. Such suffering is not necessarily about the pain of childbirth in the first instance, a pain that in any case can now be ameliorated through epidural anaesthesia. After all, in listing the effects of the Fall on human nature, the Catechism of the Catholic Church emphasises the spiritual shift that occurred, so that the body, for instance, is no longer subject to the soul’s spiritual faculties (para 400). And Saint John Paul points out that the procreation of children is closely linked to the task of handing on a way of life to one’s children.6

At the start of the Book of Samuel, we see that Hannah experienced great suffering through her infertility. Her sorrow prevented her from participating fully in the worship of God within the temple at Shiloh. But it was in pouring out her soul to God in prayer that she found consolation. She experienced a conversion of heart, and it was this that made the difference. She entered into heartfelt prayer, and made over to God any child that she might bear. It was in this way that the burden of infertility was lifted, even before she conceived her son Samuel. Sorrows that are borne with the Spirit of God are no longer the burdens they might have been. Sarah’s experience of the birth of Isaac is similarly noteworthy, as Granados comments in his discussion of Abraham’s fatherhood.7 Sarah saw the bearing of her child as an occasion for joy: “God has given me cause to laugh; all those who hear of it will laugh with me.” Her child was evidently a gift from God, as Sarah had long left behind her child-bearing years. It was, again, the action of God that was central to this change from sorrow to joy.

We can contrast these experiences with the classic biblical story of children as a cause for sorrow, which follows immediately after Hannah’s story. In 1 Samuel 2 the sons of the priest Eli go their own way, refusing to worship God under the direction of their father. Eli dies under the judgment of God as a result of his failure to discipline his sons. Death comes both to Eli and to his sons, just as it did to Adam and Eve.

“Sorrows that are borne with the Spirit of God are no longer the burdens they might have been, as Hannah’s story shows us”

St Paul’s words to children and parents in Ephesians 6 are also instructive. They follow on from the text at the end of Ephesians 5 which Saint John Paul accorded a central place in his theology of the body. The Pope emphasised that St Paul’s teaching means that a husband and wife are both obliged to give way to each other out of reverence for Christ. But St Paul goes on to ask parents to correct and guide children “as the Lord does” (Eph 6:4). Paul here is seeking to address the alienation that exists between parents and children, mirroring his teaching in relation to the alienation between husband and wife. Saint John Paul indicates that life lived in obedience to Christ forms a part of “the mystery hidden from eternity in God and revealed to mankind in Jesus”.8 We can say with St Paul, as he indicates earlier in the same letter: “We are God’s work of art, created in Christ Jesus to live the good life as from the beginning he had meant us to live it” (Eph 2:10).

Here Comes that Dreamer

One thing that makes pain especially hard to bear, though, is when it is deliberately inflicted on us by others. We see this in our starting text above from Genesis, in the phrase: “he will lord it over you”. The Hebrew word mashal for the phrase “lord it” clearly includes the possibility that the husband will act as a tyrant over his wife. The word mashal is indeed often used in this sense in the Book of Isaiah. We see suffering of a comparable nature in the story of Joseph. Like Christ, Joseph suffered rejection at the hands of his brothers. They cast him into a pit and sold him into slavery, cutting him off from the life of his family. And as a slave he suffered persistent temptation and then imprisonment.

But we also see in this story inklings of a way to dispel our perplexity over suffering. For one thing, Joseph gained maturity through his suffering: he ends the story as the master of Egypt. On another count, it is only through Joseph’s suffering that Jacob and his family escape from death by famine. Joseph himself was able to perceive that his own suffering had led to a great grace for his family, as he told his brothers: “Do not reproach yourselves for having sold me here, since God sent me before you to preserve your lives” (Gen 45:5). When Joseph looked at his suffering he did not see the evil of his brothers, but the action of God. Pope Benedict was wonderfully clear on this point in his own teaching: “God’s initiative always precedes every human initiative and on our journey towards him it is he who first illuminates us, who directs and guides us, ever respecting our inner freedom.”9

It is clear that Joseph is a member of the people of Israel, and that God reached out to him for the sake of this family. After all, the whole story began with Joseph’s obedience to his father, who sent him to take food to his brothers. All the encounters that follow are extensions of this initial act of love, whether serving Potiphar, evading the attentions of Potiphar’s wife, interpreting dreams or testing his brothers. Love bears all things. There are similarities, again, with the way that Jacob experienced his work. His seven years of labour paved the way for union with his beloved. Jacob worked for Rachel. We can call his work “nuptial” in a similar sense to that used by Pope John Paul in referring to the nuptial meaning of the body.10

We further see that Joseph possessed the Spirit. Joseph is the one who dreams and who interprets dreams, through the gift of God. Pharaoh himself says of Joseph: “Can we find any man like this who possesses the Spirit of God?” (Gen 41:38). St John Paul indicates of life after the Fall: “The body is not subordinated to the spirit as in the state of original innocence. It bears within it a constant centre of resistance to the spirit.”11 The Pope suggests that in Christ it is now possible reach a maturity whereby one’s interior life is fully attuned to the prompting of the Spirit.12 St John of the Cross, meanwhile, in the Ascent of Mount Carmel teaches us a specific path by which we might attain this inner mastery through self-denial and contemplative prayer. Indeed, on reaching the summit of union with God in this life, St John of the Cross teaches, all one’s initial impulses emerge in accordance with the will of God.13

This transition reaches maturity in those who have achieved a transparent mastery of the spirit over the movements of the flesh. We can only exclaim with St John of the Cross: “O souls created for this and called to this, what are you doing?”14 But St Teresa is equally aware that the ascent of Mount Carmel begins with conversion. After describing the horrific state of those in mortal sin, she pleads: “O souls redeemed by the blood of Jesus Christ! Learn to understand yourself and take pity on yourselves! Surely if you understand your own natures, it is impossible that you will not strive to remove the pitch which blackens the crystal?”15 For St Teresa, such self-knowledge is essential if one is to enter into the life of grace.

When Christ encountered the woman of Samaria, with her five husbands, he called her to conversion. If we are able to accept the difficult circumstances that we experience in our families as gifts from God for our conversion, then there is hope. As a Church, we need to find ways to meet those who have experienced the emptiness of sin and death, so that they too can encounter Christ. It is only in a union of love with God that we are able to experience for ourselves that creation is indeed good. Gerard Manley Hopkins speaks of the “juice” and “joy” that is present during the season of spring as “a strain of the earth’s sweet being in the beginning, in Eden garden”.16 May God grant us the grace to share in Hopkins’ vision of creation.

Dr Peter Kahn writes regularly for the Catholic Truth Society and is the author of the CTS booklets “Passing on Faith to Your Children” and “Work and the Christian Family”. He chairs of the academic council at the School of the Annunciation, the centre for the new evangelisation at Buckfast Abbey in Devon. He is also director of studies for the doctor of education programme in higher education at the University of Liverpool. Peter is married to Alison. They have seven sons.

Notes:

1Granados, J (2006). Toward a theology of the suffering body, Communio, 33, pp540-563.

2Granados, J (2006). Toward a theology of the suffering body, Communio, 33, pp540-563.

3Kahn, PE (2010). Work and the Christian Family, Catholic Truth Society, London.

4The experience of Tobias and Sarah in this regard is considered further in the booklet Timpson, J (2012). Sex Education: A guide for parents, Catholic Truth Society, London.

5Kahn, PE (2015, forthcoming). Facing Difficulties in Christian Family life, Catholic Truth Society, London.

6Pope John Paul II (1981). Familiaris Consortio, Apostolic Exhortation, Vatican City,

para 28.

7Granados, J (2006). Toward a theology of the suffering body, Communio, 33, pp540-563.

8Pope John Paul II (1997). The Theology of the Body, Pauline Books, Boston, p311.

9Pope Benedict XVI, General Audience, November 14, 2012.

10Pope John Paul II (1997). The Theology of the Body, Pauline Books, Boston, pp60-3.

11Ibid, p115.

12Ibid, pp171-3, p241.

13St John of the Cross, Spiritual Canticle, trans E Allison Peers, Westminster, Maryland, Newman Press, stanza 27.

14St John of the Cross, Spiritual Canticle, trans E Allison Peers, Westminster, Maryland, Newman Press, stanza 39.

15St Teresa of Avila, Interior Castle, trans E Allison Peers, Burns and Oates, London, First Mansions, 2, p206.

16Hopkins, Gerard M (1918). ‘Spring’ [online, accessed 29 December 2011],

www.bartleby.com/122/9.html.