What Makes Man Unique in God's Creation

Stephen Dingley FAITH MAGAZINE September - October 2015

Stephen Dingley examines an essential question, frequently raised in debates and discussions about the nature of human life, and why humans matter.

Psalm 8 is a beautiful reflection on God’s creation and it asks an important question:

When I see the heavens, the works of your hands,

the moon and the stars which you arranged,

what is man that you should keep him in mind,

mortal man that you care for him?

What is man? To start with, we are animals. We are continuous with the rest of the physical creation. We have eyes and ears and muscles which are clearly like those of kangaroos and pandas; we are made of cells just like slugs and bananas; we are made of protons, neutrons and electrons just like washing machines and planets.

On the other hand, this does not mean we are merely animals, any more than we are merely heaps of fundamental particles. But we cannot ignore the obvious truth of our animal nature. Nor is it helpful to avoid the burning question which this fact raises: the origins of the human body. The overwhelming scientific opinion is that our bodies have come about through the natural processes of evolution. Nevertheless, some people even today deny human evolution, hoping to be good, orthodox Catholics—which is laudable in itself, but it leads to many problems.

EVOLUTION

The fact of evolution—that different species of life share a common natural origin—is beyond reasonable dispute. The evidence is overwhelming. Rocks of different ages contain fossils of different species. Many species show vestigial structures from their ancestry, for instance the remnants of limbs in some snakes. Above all, the astonishing similarity of living things, anatomically and genetically, demands an explanation. And whilst a supernatural cause can always be invoked, natural causes should not be overlooked. If two students hand in identical essays, God may have inspired them to write the same words, but it’s a pretty safe bet that some copying has been going on!

The basic motivation for denying evolution is fundamentalism—the tendency to interpret the scriptures completely literally, refusing to allow any symbolism or figures of speech. We should respond first by pointing out that this places unwarranted limits on how God can choose to communicate with us. But it is clear from a careful reading of Genesis that a naïvely literal interpretation is impossible. For example, in chapter 1 the plants are created before man; in chapter 2 they are created afterwards.

ST AUGUSTINE

Saint Augustine of Hippo was remarkably insightful about this nearly 1500 years before Darwin. He points out that the “days” of creation cannot be understood literally because days are defined by the passage of the sun—and the sun was not created until day four! He is also clear about the disastrous effects of denying scientific knowledge in the name of religion:

Usually, even a non-Christian knows something about the earth, the heavens, and other elements of the world … Now it is a disgraceful and dangerous thing for an unbeliever to hear a Christian, presumably giving the meaning of Holy Scripture, talking nonsense on these topics … How are they going to believe these books in matters concerning the resurrection of the dead, the hope of eternal life, and the kingdom of heaven?

An authentic reading of Genesis even lends some support to the idea of evolution. For Adam’s body was not created directly from nothing but “from the dust of the ground” (Gen 2:7), that is, from something else that God had already created. Similar ideas are found for the animals: “Let the earth bring forth living creatures.” (Gen 1:24) Pope Pius XII, St John Paul II and the Catechism have lent increasing support to scientific views of the origins of the human body. The question of the soul, however, is another matter, and it is to that question we must now turn.

CONTINUITY AND DIFFERENCE

Having established the continuity between ourselves and the other animals, what are the differences—for they are many? For a start, sport. We are (seemingly) insanely interested in people we don’t know kicking balls between wooden posts or cycling around France for three weeks! Then there is culture: music, art, television, video games. We love exploring, be it going to the moon or just on holiday for a couple of weeks. We spend vast amounts of money and effort on science. Some of it we put to use in technology, but much ‘big’ science is for the sheer love of knowing how the universe began or what atoms are made of.

Two more characteristic features of human life are vital to mention. Firstly, we understand our actions to have absolute moral value, above and beyond their practical usefulness, and irrespective of whether we get found out! Our actions are absolutely good or bad. And we understand ourselves to be personally responsible for our actions, unlike the animals. For instance, we may put a dangerous dog down, but we blame its human owner for not controlling its bad behaviour.

RELIGION

Secondly, what most distinguishes us from animals is religion. Human beings throughout world and throughout history have looked for God, or for gods. We recognise that the world and ourselves are not self-explanatory but rather need some higher cause. Where authentic religion is absent, we do not find happy rationalists but rather false religions, superstitions, addictions of one kind or another—and despair.

Animals, frankly, are only interested in the ‘bare necessities’ of life: food, shelter, reproduction, and so on. They may have very complex behaviour, but it is essentially focused on biological needs. They just don’t go to concerts or football matches or church. We have biological needs too, and they are important to us. But ultimately we get bored with things of only biological relevance. They are not the meaning of our lives, not the things we cherish dearly. When through force of circumstance people’s lives have to focus exclusively on their biological needs we say they have been “reduced” to poverty. The phrase is telling.

TRANSCENDING

All of this means that we transcend our material makeup as animals. Being animals is not enough for us. We transcend control by our physical environment and our biological instincts. For example, we have an instinct to eat, but we can choose to fast instead. In other words, we have free will. Our bodies obey the laws of science, but we are not simply controlled by them—there is more to say. We are not robots.

What we choose to do is irreducibly personal: it cannot be fully understood in terms of external influences, brain chemistry, and so on, although these have a part to play. Nor are our actions random—free will is not about being chaotic. This idea of freedom has a certain mysteriousness for us. We cannot understand it in terms of the material world around us, because matter is not free. Matter obeys the laws of science, and that’s all. But when we honestly consider the meaning of our lives and our actions, that can’t be all.

LOOK FURTHER

So if we try to understand the difference between ourselves and the other animals, we need to look further than our brains. It is true, our brains are about three times larger than would be expected for a primate of our size. But brains are material things. Bigger brains just make smarter animals. In fact, however you study human beings in biology, whilst you will find out true and important things, you will never really understand what it is to be human—you will miss the point. The rational conclusion seems to be that we are more than just bodies, more than just animals. We have something else as well. We have spiritual souls.

This, then, raises the deeper question of how humanity came to be. It is a question which is vital to the theological system advocated by the Faith Movement. The key idea of this theological vision is that the whole of God’s plan for creation and salvation is expressed by a single wisdom or ‘law’, governing and directing all things—matter and spirit—to their fulfilment.

THE BIG BANG

From the Big Bang until the threshold of humanity this law takes the form of the laws of science, which ultimately bring about the emergence and evolution of life. Since evolution is controlled by the processes of natural selection (or, loosely, “survival of the fittest”) any physical characteristic will only develop within the parameters of what is biologically useful. Further development would be wasteful or harmful, and would not be naturally selected. This presumably applies to the brain too. However, as we have already seen, we understand the meaning of our minds in ways which go beyond biological relevance.

It seems reasonable, therefore, to suggest that the mutation for greater brain power than is biologically meaningful was not selected naturally. Instead, this is the moment God had planned all along at which to infuse the spiritual soul. The soul is therefore not an ‘optional extra’ or a gratuitous addition to our animal nature. The human body does not fully make sense without a soul—indeed, without the spiritual soul it dies. It would be meaningless and foolish for God to give a spiritual soul to a cat or a cabbage; but it would be equally foolish not to give a soul to a human body.

THE SOUL

It follows that the soul did not evolve. Evolution is a material process governed by the laws of science. And, by definition, the soul is that aspect of man which goes beyond matter. The soul must be directly given by God; given first probably some 150,000 years ago; given every time a human being is conceived. This is the moment at which God’s ‘law’ begins to operate at the spiritual level as well as the material.

Finally we can delineate what the soul gives us. Firstly, it gives us free will—the capacity to choose what we do on the basis of our experiences and feelings, without being automatically controlled by them. Freedom makes us morally responsible for our actions; it also makes us capable of love—for true love must be free gift. Freedom, however, can be abused. We can disobey God’s law, which the animals cannot. Next, the soul gives us real intelligence—the ability to know the truth and value of things absolutely rather than just in terms of their pragmatic use for ourselves. Finally, because the soul is not material, it cannot decay in the way material things do. The soul is therefore immortal and gives us hope of life after death.

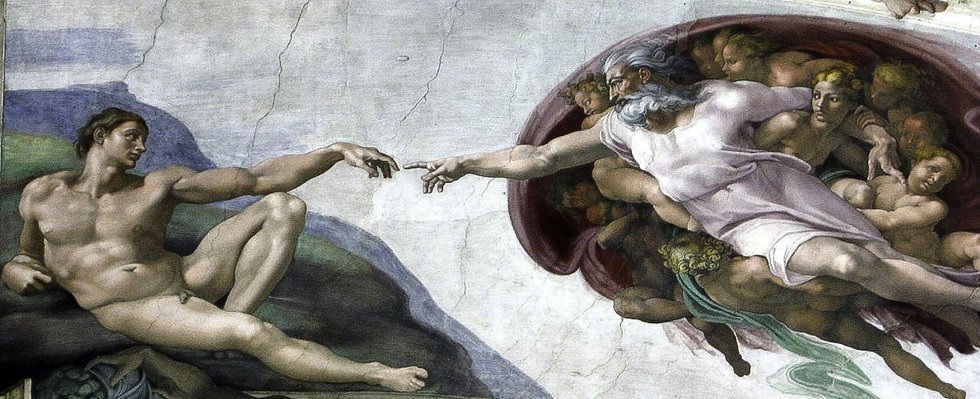

Thus our souls make us persons rather than just things, made in the image and likeness of God (cf. Gen 1:26-27). We have infinite value, from conception to bodily death and beyond. We should be infinitely valued by others; we are infinitely valued by God. He has made us to know Him and love Him personally, and for all eternity. It means therefore that religion is natural to us, as St Augustine famously commented: “You made us for yourself, and our hearts find no peace until they rest in you.” It means that God is our true ‘environment’. We need God more than we need food and water. For only God can really satisfy our deepest and most human yearnings, for absolute truth and absolute love.

Fr Stephen Dingley STL is Professor of Theology at st John's Seminary, Wonersh.