The Impact of the Real: Holloway's Realignment of Thomism

Dr Gregory Farrelly and Fr Hugh MacKenzie explore the phenomenological foundations of Edward Holloway’s realist philosophy.

Fr. Edward Holloway produced a wealth of theological writings concerning a new syn- thesis of orthodox Catholic theology and modern scientific/philosophical thought[1]. In later life, he was able to develop his philosophical ideas. These were published in three slim volumes entitled Perspectives in Philosophy (available from https://www.faith.org.uk/shop). These later works develop the ideas presented in his earlier, primarily theological, work, Matter and Mind, written four decades earlier.

Philosophy is 'the handmaid of theology' and is essential for theological explanation, in a way that is analogous to the use of mathematics in physics. Holloway attempted to update the scholastic philosophy of Aristotelian science in the light of experimental methodology and the 18th century 'turn to the subject' initiated by Kant. It enabled him to fine-tune aspects of traditional presentation fo the faith, such as the description of human nature, the proofs of the existence of God, and, ultimately, the idea that all reality is centred upon Jesus Christ.

New Philosophy

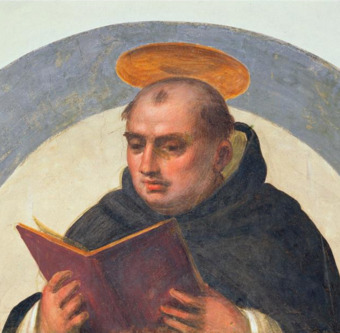

![]() Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) built his theological synthesis on the basis of Aristotelian philosophy. The key works of Aristotle had been rediscovered in the West through translations from Arabic texts commissioned by Muslims in the tenth century. At the time Aristotle was considered the 'latest word' in physics. Aquinas successfully showed that Aristotle could be used to underpin the intellectual credibility of Christianity. Aquinas’ theology and philosophy (known subsequently as Thomism) became the bedrock of the Church's explanations of the faith, bearing great fruit in medieval culture. Until recently it was taken for granted as the best philosophical basis for Catholic Theology.

Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) built his theological synthesis on the basis of Aristotelian philosophy. The key works of Aristotle had been rediscovered in the West through translations from Arabic texts commissioned by Muslims in the tenth century. At the time Aristotle was considered the 'latest word' in physics. Aquinas successfully showed that Aristotle could be used to underpin the intellectual credibility of Christianity. Aquinas’ theology and philosophy (known subsequently as Thomism) became the bedrock of the Church's explanations of the faith, bearing great fruit in medieval culture. Until recently it was taken for granted as the best philosophical basis for Catholic Theology.

The early 17th century, however, witnessed the birth of experimental science which was to bring about a major change in the worldview that was familiar in the middle ages. As Francis Bacon and the Royal Society trumpeted, the new approach to understanding the physical was induction, not deduction, drawing data from carefully repeated observations. The change of emphasis was confirmed by the transformation of geometry from the neat somewhat stagant, syllogisms of Euclid into world changing measurements of calculus. New philosophical approaches also arose from this. Bacon showed that the scholastic notion that we identify things by "abstraction" of the universal "form" from our sensation of them, is not correct. We discern a “Pyramid” of Forms by repeated observation. Nominalism gained impetus from this rejection of static, abstracted ‘universal’ Forms. For the luminaries of the burgeoning Royal Society, universal Forms were just general ideas, mere names (hence nominalism from the Latin nomen/name) without any corresponding reality. The implications of this epistemological revolution provoked a reaction among Catholic thinkers, notably Descartes (1596-1650). He proposed that we innately attain to the most universal ideas (like the concepts of “substantiality” and “unity”) before we actually sense physical objects.

Descartes therefore, triggered a switch of methodological starting point of philosophy, from the sensed world as observed, to the human subject as observer. This “turn to the subject” was worked out in the philosophy of Hume, Kant (both 18th century), Hegel (19th century), Husserl, Heidegger and other 20th century Existentialists. Kant himself called it a Copernican Revolution, because whereas the Greek mindset roots ontology in the patterns of the physical object, he tried to root it in the impct upon and action of the subect. Instead of Forms 'out there' being at the heart of reality, the subjective experience of moral imperative and the resutlant subjective action was.

A positive aspect of this movement for Holloway is that it referred the significance (or “meaning”) of the objective to its impact upon and evaluationby the subjective mind. Einstein illustrated this when he was asked to describe his theory of Relativity in one sentence. He replied, “If you sit on a hot stove for one minute it seems like an hour. If you sit with your beloved for one hour, it seems like one minute.” The meaning of objective time is far from exhausted by counting it. Time and space, which are interwoven into the unity of the envrionment of the human observer and actor, are aspects of potential for personal interaction, it is not that personal iteraction simply fits into a static, linear, a priori formal matrix.

But a negative feature of this line of philosophical development is the deprecation of the idea that things have objective "natures". This concept is crucial for the understanding of human nature and thus of Man's salvation in Christ. Its rejection by the broad, influential school of nominalism, we would contend, has resulted both in the pervasive individualism and relativism of today's secular culture and in the fideism of many modern believers.

The 1960s

In the 1960s, the Nouvelle Théologie started to take root. In some ways this took account of the newly discovered dynamism of physical things. But it didn’t update the notion of ‘Form’ and so failed effectively to challenge nominalism. Its synthesis of modern philosophy and Catholic theology couldn't ground the better proofs of the soul and God that was needed to restablish the harmony of faith and reason. We have, in fact, seen an acceleration of indifference towards the truths of Catholic doctrine in popular culture and its dismissal as irrelevant in the eyes of influential scientists and philosophers. At the heart of this intellectual maelstrom is the question of the nature of "the real" and of its relationship to the human subject.

Recent Decades

Somewhat inspired by the unchecked rise of nominalistic philosophy of science, more recent times have seen the rise of influential proponents of scientific atheism. They argue that the philosophical implications of modern science preclude the existence of God and eternal life. This view is not only prevalent among western intellectuals and scientists, such as Lawrence Kraus, Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett and Sam Harris, but is also highly influential among sincere and enquiring young people. On the other hand, there has also been a reaction to this de-natured world-view among anglophone philosophers of science, even a new respect for aspects of Aristotle’s metaphysics[2]. Somewhat encouraged by this, neo-scholastic Catholics, such as Edward Feser[3] and David Oderberg[4] have attempted to save the old concept of knowable, universal “Form” as something metaphysically distinct from individuating matter[5].

Holloway’s Contribution

Edward Holloway had a great respect for the achievement of Scholasticism in making philosophy the handmaid of a theology which reverenced Revelation. But he also acknowledged, with the Second Vatican Council, that, “the human race is passing from a rather static concept of the order of things to a more dynamic, evolutionary one … calling for efforts of analysis and synthesis.”[6] So, he was particularly interested in developments of the Nouvelle Théologie, not least the work of Henri de Lubac. He also engaged with Henri Bergson’s attempt to synthesise modern philosophy’s turn to the subject with the reality of evolution[7]. While sometimes calling himself Existentialist and partly situating himself within post-Kantian phenomenology, he affirmed that human language, and therefore the human mind, can connect with what is objectively real. For most Existentialists, meaning[8] is rooted in the pre-conceptual realm of purely subjective experience and creative action. This subjective experience is seen as "transcendent” of the objects of human concepts. Where Kant's focussing upon humanly supplied categories about physical objects led to a rejection of meta-physics, the Existentialists reintroduced it. But Holloway pointed out that the resultant undermining of the ability of human sentences to capture unchanging, doctrinal truth, was contradictory. He argued that it was this which undermined Karl Rahner's otherwise important attempts at a new synthesis of such continental philosophy and Christian revelation.

In like manner to Aquinas, Holloway sought above all to provide a modern philosophical defence of realism (that language can capture truth) and of human nature[9]. He wanted to give full weight on the one hand to the insights of modern philosophy and the resultant turn to the subject, and on the other hand to the truths of revelation and the Magisterium regarding the place of human nature in God's divine plan. The fact that Jesus shares our human nature is a key point for a synthesis of philosophy and theology. This is because Catholic explanations of the Paschal Mystery are necessarily founded upon the fact that Jesus Christ shares the same nature as us.

The Mind to Matter Relationship

Holloway roots his vision in the neo-phenomenological insight that as human beings we affirm our own existence in a distinct environment[10] – akin to Bergson’s “method of intuition” of distinct things. This grounds a key two-sided concept of his: spiritual mind controls and directs matter, and matter is controlled and directed by mind into layered unities, through physics, chemistry, biology, the life sciences, ecosystems, planets, etc[11]. These material unities, at whatever level, are in their very being that which is related to and simultaneously intelligible to mind. In his latter writings Holloway develops this basic intuition to affirm matter as a mediation between the Mind of God and mind of Man[12].

Kant (in the standard interpretation) affirmed that the object of our experience (the ‘phenomenon’, from the Greek passive participle) is conceptually intelligible but not actually, existentially distinct from the subject as it is understood by the subject. The phenomenon, that which the human subject perceives by sensation and intellect using a priori 'categories' of thought, was transcended by the noumenon — the 'thing-in-itself’ (das Ding-an-sich) as disitnct from and posited by the subjective "Transcendental Ego". The latter thought was intrinsically unintelligible ot us. Holloway combines these two concepts into a single act of insight. Although broadly accepting Kant's ‘turn to the subject’, Holloway rejects his view of the noumenon as unknowable and transcendent of normal, phenomenal intelligibility. Yet he maintains the distinction of the knowing subject from the (now intrinsically intelligible) thing-in-itself. They are the poles of the fundamental epistemological relationship. After all, if the noumenon (the ultimate reality of a thing) is truly unknowable, how could its existence be affirmed in Kant’s own theory of knowledge?

Holloway offers what might be termed an integrated 'noumenal phenomenology', based on a realist existential grounding of the content of the observer's experience, what he calls "the impact of the real"[13]. This also means that the existential distinction between the subject who experiences and the object which is experienced is affirmed, thereby avoiding philosophical Idealism[14]. The mind’s act of thinking is a term of a real relationship with that which is thought[15]. The knower and the known form a unity. Consciousness is of self as well as of the other. The two are distinct and inter-defined. Holloway's collapsing of Kant's epistemological analysis into a single noumenal-phenomenal experience means that the relationship of intelligibility and distinction between subject and object is fundamental and existential. As is the resultant unity between them.

The complementatory of this relationship should be emphasised. For Holloway, as for Kant, human self-consciousness does not only passively receive meaningful impacts from reality. Human perception is a developmental, existential and evaluative orientation towards the real surrounding world within which we find ourselves. Descartes' famous "Cogito, ergo sum" (I think, therefore I am) might equally be turned around the other way, "Sum, ergo cogito" (I am, therefore I think). The human person, who can certainly say “Cogito”, is simply personal 'being’ in relation to everything else. The 'Sum' [I am] is simply affirmed by self-consciousness together with its present environment, requiring no deduction. This relationshiop is what a concept is.

As Holloway writes:

"Everything starts with the perception of our own existence, our own reality... The affirmation of self-identity is that I am, I perceive, reflect, think, feel, and know: from birth and before birth the affirmation of self is dynamic, and never, never 'agnostic' in any way whatever. Beyond this dynamic self-intuition and fulfilling it, is the question who I am, and what I am ... the appraisal of the real. [… This] speaks and recognises co-relationship. ... (the] affirmation of entitative unity between the self and "the other"— "I am" is actually the very root of the idea of truth and also of the concept of nature." [16]

Holloway affirms the relationship between spiritual, embodied mind and observed physical objects as foundational not only to our perception of reality, but also to the nature of the cosmos in which we find ourselves. No metaphysics can be developed without the centrality of "the impact of the real" upon the human observer's mind and body. The categories we use are rooted in the phenomenon of mind, but they also accurately refer to existence, because all created existence is in its very nature, ultimately that which is known by mind. So, in effect, he rejects the idea of Husserl and the Phenomenologists that it is possible to 'bracket off’ the actual existence of an entity from our perception of it[17], along with the Heideggerian development of this which proposes that we do experience the actual existence of things but only in a non-categorical (pre-conceptual) fashion[18].

The problem for all these post-Enlightenment schools of thought is that they keep the static view of what Aristotle calls 'essence' and so make the basic dynamism and particularity of subjective experience a priori to abstract conceptualisation. Holloway agrees that the subject-object dynamism is foundational to any account of meaning, but for him it is also inherent to conceptualisation since particular objects make sense (are ‘meaningful’) dynamically, not statically. They are fundamentally part, with of the "other", of a higher unity, without which "I am" has no meaning (and vice versa).

And this physical other refers, we will see, to other minds.

The Ability to Act

Grasping meaning and value, seeing the significance of what is around us, enables that other key characteristic of the human subject: action. Intellect leads to will. If intelligibility is dynamic and particular (not just abstract and ‘universal’) then it is possible to affirm (with many of the Pragmatist school) that knowledge is a capacity to act. The significance of the object of our perception is, at its fullest, an invitation to act and, through our conscience, to act well. We experience our mind as a meaning-recogniser and, through our intelligent actions, we are meaning-enhancers. The content of what we know enables us to be creators upon it. Making sense leads to making the sense I want. A striking, if particular, example of this seems to be at the lowest physical level. Most interpretations of quantum mechanics (the physical theory of matter at the atomic and subatomic levels with applicability higher up) hold that the human 'observer' is necessary in any intelligible evaluation of the measurable parameters being considered[19].

One distinction between Holloway and some contemporary exponents of Aristotelian philosophy is that Holloway regards scientific truths as always having metaphysical and moral implications. This partly follows from the phenomenological insight that all perceived meaning is meaning for a subject, as per the Einstein quote above. Mathematical patterns are an intrinsic aspect (but only an aspect) of the intelligible ‘invitation’ to act well we receive from our physical environmnet. Because of Holloway’s collapse of the noumenon - phenomenon distinction, there are not for him, as for some Christian theologians and existentialist philosophers, two ultimately independent orders of legitimate thought about reality: metaphysics and natural science. For Holloway, the intuition of an object's existence is simultaneous with its intelligibility, mathematical or otherwise.

This is in tension with the scholastic Essence-Existence ‘real distinction’. He claims to follow the Scholastic dictum lex mentis, lex entis more closely than they did themselves. Intelligible, successful engagement always involves knowing a really existent entity, at whatever level of unity we are dealing – ecosystem, species, organic, chemical, molecular, etc. This insight is what makes reductionism a non-starter, and it enables Holloway to affirm realism in our perception of the holistic, hierarchical layers of the cosmos (and to explain the 'universal' term).

For Holloway, the human mind is in a mutually defining relationship with objective matter. The mind/soul immediately controls and directs the matter of its body, and which latter is thereby in a mutual relationship of control and direction with its local environmnet. This key philosophical idea, will enabel Holloway to update trations proofs of God and the soul, while holding together the insights of Phenomenology regarding the human mind's part in reality, the basic concerns of Scholastic Realism, and modern empirical science regarding the objective material universe.

An Underlying Unity-Law

The unity of anything physical arises not only through its being a part of a physical environment that is built upon nested layers of organised systems, but also from the mind which is the ultimate context for the unity’s definitive and dynamic functionality. Function needs context. Unities need environments. For example, the identity of a hydrogen atom when it is bonded within a molecule of water, certainly arises from the structure of that particular atom, but also comes from the molecule of which it is a part and the unity-function of that molecule. And if that water molecule is drunk by a cat, it now contributes to, and receives its definitive functionality from the characteristic unity-structure and constructive activity of the physical body of which it has become an organic constituent. This identity through meaningful unity speaks of a fundamental relationship to mind. And that relationship not any less real and definitive for being rooted in the non-physical. The foundational phenomenology has been show to be metaphysical.

This defining, existential relationship of an object with mind is illustrated by Holloway through considering the way humans create an artefact from existing components. We give a new holistic identity and relational function to a unity of parts by controlling and directing the parts into a new unity. It is the Mind of God that does this for the cosmos as a whole. So, for Holloway "the environment" which determines the identity of material things is both their holistic physical unity within the cosmos and the mind which is in the relationship of conferring identity. It is according to the underlying 'Unity-Law of Control and Direction’ which frames all reality.

A personal relationship

The cosmos is a unity created and held in being by the mind of God. The human mind perceives and develops the hierarchical dovetailing of functions which the Mind of God creates. God is the ultimate, transcendent Mind. Holloway calls God "the Environer" of humankind to express the level at which this Unity Law becomes a personal relationship. The physical environment is the mediator of identity, of "control and direction", but its source is the non-material "Environer", the Mind of God. For the human soul this is an immediate and wholly natural relationship.

The concept of physical mediation of unifying control and direction through evolution allows Holloway to explain two central moments in the hisotry of humanity. They are moments when, at key points of the development of God's plan, spiritual mind takes over immediate control and direction of physical unities. Firstly, the infusion of the spiritual soul is needed to control the human brain-body at the first moment of the mutation of that first human brain-body, that of ‘Adam’. The mutation created a brain to big for the environment to mediate control and direction. This will also be the case for the conception of each member of the human species. Secondly, when the ‘womb of woman’ is directly determined by the Mind of God at the Incarnation, in she who was called to give her fiat on behalf of the whole of creation. In the conceiving of God-made-flesh, His eternal identity cannot be mediated by matter. The male princile of determination is not appropriate in this case. In fact, it is the Mind and Body of the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, the Logos, that gives identity to everything else in the cosmos.

A Basic Realism

Holloway's philosophical starting point

It is a basic condition of Christian evangelisation of culture that we re-vindicate a basic realism about our new knowledge of a world that is holistic and relational, in whih also the whole is predicted by the parts.[20]. For Holloway, this newly discovered cosmos invovles the dovetailing of lower, defining functions which infer the defining functions of higher unities. His phenomenological starting point , "I am in a disitnct environment", enables us to see that they are all (relatively[21]) intelligible to mind, and thus real. For instance, the ability of some plants to photosynthesize is an irreducibly real aspect of their natures, notwithstanding the fact that the plant's structure, and the nature of light too, can be given a bottom-up explanation from the laws of physics and chemistry[22]. This approach, we would argue, can offer a better solution to the problem of "the universal" and of "natures", than a Thomist "moderate realism" with its Aristotelian concepts of matter and form.

Holloway has a clear belief in the reality of objective entities which exist through their relationships with each other, as do most scientists. His dynamic metaphysics forms the basis of his proofs of the transcendent human mind in the spiritual soul, and of God's existence as Supreme Mind and loving Environer. The matter-spirit distinction is existential, not merely metaphorical. In fact, it is basic to all meaning in the cosmos.

Dr Gregory Farrelly is a Physics teacher. Fr Hugh MacKenzie is currently working at Westminster Cathedral and finishing a PhD.

[1] Fr. Roger Nesbitt, co-founder with Fr. Holloway of the Faith movement, drew this out in recent issues of this magazine [Sep/Oct and Nov/Dec 2020]

[2] For example, Cartwright, Nancy. The dappled world: A study of the boundaries of science. Cambridge University Press, 1999; R. Harré, “Powers”, The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, Volume 21, Issue 1, Feb 1970, pp 81–101;https://doi.org/10.1093/bjps/21.1.81

[3] Aristotle's Revenge: The Metaphysical Foundations of Physical and Biological Science (Editiones Scholasticae, 2019).

[4] Oderberg, Real essentialism. Routledge, 2007.

[5] But this doesn’t cohere with Cartwright et al, as we hope to show in a future piece, yet still defending the reality of universality and singularity. In PiP, Vol 1, Holloway repeatedly bemoans that the this hylomorphic distinction did not respect their own saying “lex mentis, lex entis”, “for I perceive in my mind that I know only the determinate, the real, the singular … this man, not ‘humanitas’ or ‘homo’ ( p.22).

[6] Pastoral Constitution on the Modern World, Gaudium et Spes, 1965, n.5

[7] H. Bergson, The Creative Mind, tr., Mabelle L. Andison, New York: The Citadel Press, 1946, p.175-187

[8] The fact that things ‘make sense’ to the mind of a subject, thereby (for Pragmatists and Holloway) enabling them to act. And Cf. n. 10.

[9] PiP Vol. II, p. 3 claims to be presenting a philosophy that is a “new, existential rethinking of the cosmic unity ... It is usually said that systems of Existentialism of their very perspective, deny the recognition of essence or ‘nature’. We can show this to be scientifically, as well as philosophically, untrue.”

[10] Ibid., p.70: “All our philosophizing if it is going to be true, i.e. measured as an equational harmony with the real, must begin from, and reverence, the initial existential experience of ‘being’."

[11] For Holloway, the spiritual order of being is simply made up of personal minds. Mind is a controller and director, whether through the human soul, the angelic being, or the very Being of God – in the latter case we capitalise the ‘M’. There are no metaphysically distinct “Forms” in Holloway’s metaphysics. PiP Vol. 2, p.70: “the analogy of being in the order of the ‘soul’ between God and Man or Angel, does pass beyond the essential into the existential order, the conscious order of the self”. Bacon’s above mentioned discernment of a “Pyramid of Forms” was not a million miles from the truth.

[12] His is an ontological enrichment of Newman’s moral evaluation of the “nature of things”. As Holloway said, “As far as ‘I’ am concerned, even God exists unto me because first of all I exist myself”. Newman said, “From a boy I had been led to consider that my Maker and I, His creature, were the two beings, luminously such, in rerum natura …I believe in a God … because I believe in myself … I feel it impossible to believe in my own existence … without believing also in the existence of Him, who lives as a Personal, All-seeing, All-judging Being in my conscience” (Apologia, 1993, Everyman, Ch.IV, sec.2, pp. 238; 241)

[13] This theme is introduced in “The Impact of the Real”, Chapter 2 of the second volume of Perspectives in Philosophy, and developed in the third volume, which has the subtitle “Noumenon and Phenomenon in the Age of Modern Science”.

[14] PiP Vol. II, p. 71 has, “The philosopher must beware of establishing his methodology from too cerebral, too a prioristic a pitch.”

[15] “We postulate the other as ‘other’ only in an existential polarity to the ‘self’… The awareness of the myself consists in that which I sense, think, feel, and above all control with self-determination … There are so many existential impacts upon my existence … which I do not con-trol and over which I do not exercise this unity-in-existentiality which is myself. These ‘so many’ impacts I call ‘the other’". (PiP, Vol. II, p.71)

[16] PiP, Vol. II, pp. 6-7

[17] “In phenomenological reflection, we need not concern ourselves with whether the tree exists: my experience is of a tree whether or not such a tree exists.”, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/phenomenology/, 8/1/21

[18] The existential phenomenologist Heidegger was a huge influence on the Jesuit theologian Karl Rahner, whose theology influenced directly or indirectly much of the ‘new’ approach to catechetics that, one might claim, played down the irreformability of Christian linguistic statements of revelation.

[19] Technically, this may be considered the ‘cause’ of ‘quantum decoherence’ or ‘collapse of the wavefunction’.

[20] This turns out to be a phenomenological development of the contemporary “Powers” philosophy of modern science which we hope to explain in a further article.

[21] Holloway believed in an ‘analogy of being’ concerning physical things. He saw the chased rabbit’s relation with escape routes as ‘higher’ than water molecules (cf. Edward Holloway, Catholicism: A New Synthesis, Faith-Keyway, 1976, pp.42; 54): “If the reinstatement of the notion of potency, of tendency to become, is proving of help in the philosophy of science, so too the restoration of the concept of the analogy of being will prove to be of service. The concept of analogy means that the existent real is more or less intelligible in its very self, according to the degree of intelligibility in which its existence is actualised … The rabbit … is itself being in a sense deeper than an electron in as much as it is less potential.”

[22] PiP II, p.6-8 has, “There is in judgment … an affirmation of entitative unity between the self and the ‘other’. [More generally] entitative relationship means … the basic relationship of communion in being and becoming between ‘things’ whatever things may be … “I am” as self-identity exists in different degrees of intrinsic proportion in all things: in sentient life lower than man, in matter below life, matter in the first formulation of the universe ... All created being intuits itself in its identity principle as co-relative. It moves and is itself a mover. It is changed and it causes change”