What has Ethiopia to Teach us?

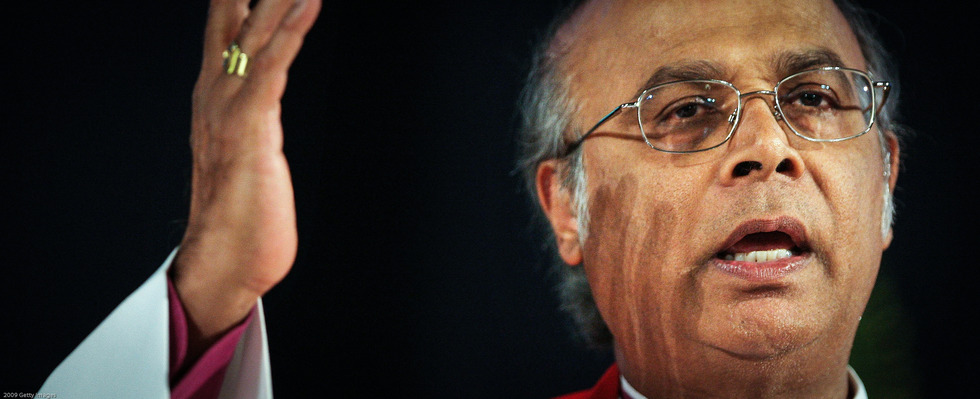

Bishop Michael Nazir-Ali FAITH MAGAZINE July-August 2014

The introduction of Christianity to Ethiopia is charted in the Acts of the Apostles. The contemporary story of this ancient Christian church, though, has much to teach us, says Bishop Michael Nazir-Ali.

The St Frumentius Lectures in Addis Ababa are named after one of the two missionaries who re-evangelised the Empire of Abyssinia or Ethiopia in the fourth century. The other was Aedesius.

This year I was invited to deliver these ecumenical lectures on the theme of Christians in public life. Naturally, this brought me into contact not only with representatives of the churches but also with government ministers and officials. Like all other travellers to this remarkable country, I was fascinated by it. Here is an ancient civilisation which was once dominant across the Red Sea in South Arabia but also in Egypt. Although the arrival of Christianity systemised and propagated a written language, a literary tradition had existed before it, as had various forms of art.

Ethiopia is a prominent example, among others, of the early inculturation of the Gospel in contexts that were entirely non-Hellenistic. It may well be, as Pope Benedict claimed, that Christianity’s encounter with Hellenism was providential, providing the Church with the linguistic and philosophical tools to engage with the Graeco-Roman world. There were other significant encounters, however. The Syrian, Coptic, Indian and Armenian come to mind. The Ethiopian is yet another.

“The overthrow of the last emperor, Haile Selassie, in 1974 led to a period of being in the wilderness for the Ethiopian Orthodox Church”

In terms of what John Paul II has called the “continuing missionary mandate” of the Church, these examples are important today for the growing churches of Africa, Asia and Latin America as they learn how to engage the Gospel with the cultures in which they find themselves, so that the cultures themselves, as well as the churches, are transformed and renewed.

The Ethiopian Church is unique in its liturgy, canon law and customs and, at the same time, maintains important links to the Church in other parts of the world. On the one hand, it observes the Jewish Sabbath, as well as the Lord’s Day, and retains a number of other Judaic practices, such as circumcision and the distinction between “clean” and “unclean” food. Many African features can also be observed in, for instance, liturgical music and dance. On the other hand, many of the Church’s feasts and fasts are recognisably those of wider Christianity. The psalms are widely used in worship and private devotion and the basic Eucharistic Prayer is none other than that of Hippolytus of Rome!

Along with Armenia, Ethiopia was one of the first nations to call itself Christian (Western Christendom came much later). This means that there has been a kind of “establishment” of the Church in Ethiopia for centuries, with clergy and monks involved in the affairs of the state. The overthrow of the last emperor, Haile Selassie, by a Marxist-inspired coup in 1974 introduced a period of being in the wilderness for the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, which along with other churches experienced martyrdom and persecution.

The present regime claims to be secular, deriving its values from the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and “neutral” in respect of the different religions of Ethiopia. A number of questions arise regarding this attitude. Namely, from where have the values enshrined in the UN Declaration come? Do they derive from the Judaeo‑Christian tradition and do they make sense only in the context of a biblical world view? Will they survive if they are permanently detached from the context which has given rise to them?

These are questions not just for Ethiopia but for all so‑called "secular” societies which are content to live in the afterglow of Christian values, believing they will outlast the faith which produced them. Will they, or will we, be engulfed by a new Dark Age?

Another point made by the government is its adherence to Article 18 of the UN Declaration, which guarantees freedom of belief, freedom of conscience, the right to manifest our belief in public, etc. Will these freedoms be respected and will all religions in Ethiopia subscribe to this Article? It is noteworthy that equivalent Islamic declarations omit the safeguards of Article 18 altogether. Again, we can ask whether the spate of hate-speech and “equality” legislation in Britain and other European countries – not to mention the restrictions on public manifestations of faith, the right to which has been upheld again and again by both domestic and European courts – also falls foul of this Article.

“The overthrow of the last emperor, Haile Selassie, in 1974 led to a period of being in the wilderness for the Ethiopian Orthodox Church”

Since receiving the first refugees, sent by the Prophet of Islam himself, Ethiopia has had a special relationship with Islam and with Muslims. Will future relationships develop in the context of this tradition or in the direction of the conflict which has also been endemic between Ethiopia and neighbouring Muslim lands? At the moment, there is a precarious balance between Muslims and Christians, with Muslims making up some 34 per cent of the population and Ethiopia being courted by some of the oil-rich Arab states. The Tablighi Jama’a and other Muslim missionary organisations are active and there is the possibility of conflict between them and ultra-Orthodox movements. At the same time, the Evangelical churches are growing rapidly. This could be an occasion for a new ecumenism or it could open another chapter of intra-Christian conflicts. Again, Ethiopia has a great deal to teach us, if only in reflecting some of our own problems back to us.

We cannot idealise the Church or the state there, but we can be thankful for the rich history of both – and for the many lessons they can teach us in the West and in the world of Islam.

Bishop Michael Nazir-Ali is the Anglican Bishop-Emeritus of Rochester. He has both a Christian and a Muslim family background and is now President of the Oxford Centre for Training, Research, Advocacy and Dialogue.